50 Common Climber Mistakes (And How To Avoid Them)

I’ve been climbing for more than 15 years, and the mistakes I’ve made cover the gamut. My knot came partly untied while I was climbing at Joshua Tree; I’ve threaded my belay device backward; partway up El Capitan, my partner once completely unclipped me from a belay. Worst, I dropped a dear friend while lowering him off a sport climb in Rifle with a too-short rope. (Fortunately, he wasn’t seriously injured.) If you’re lucky, like I’ve been, your mistakes result in close calls that help keep you vigilant. If you’re not, the results can be tragic.

Not all errors in climbing are deadly— some may just sour your own or

other climbers’ experiences. But if you never learn from your

screw-ups—and other people’s—you’ll be slower to improve. In climbing,

as in life, bad experiences are the foundation of good judgment. With

this in mind, we’ve assembled 50 of the most common mistakes made by

climbers everywhere—and suggested how to avoid them—in hopes of speeding

your journey toward being a safer, smarter climber.

NEVER-EVER MISTAKES

1. Not double-checking your belay and knots

If you’re belaying, make sure the rope is threaded correctly through the

belay device and that the locking carabiners in the system are actually

locked. If you’re the climber, double-check your knot. Is it tied

correctly? Is it tightened? Threaded through the harness correctly? Is

the tail long enough? Check your partner’s knot, too.

REAL LIFE: One famous double-check mistake was Lynn Hill’s accident in Buoux, France, in 1989. When Hill—already a 5.13 climber at the time—weighted the rope at the top of a warm-up climb, her unfinished knot zipped through her harness. She fell 75 feet to the ground but survived. Hill says she got distracted by a conversation and forgot to finish the knot; a bulky pullover hid the error.

2. Not wearing a helmet

Trad climbers wear helmets much more often than sport climbers, but why?

You can deck, slam the wall, or flip upside down in sport climbing, and

loose rock is always a hazard. Evaluate all the risks before you make a

fashion-based decision not to protect your head.

3. More confidence than competence

Push yourself to become a better climber, but understand the risks and

assess your ability to mitigate them. The American Alpine Club rates

“exceeding abilities” as one of the top causes of accidents.

4. Careless belaying

There are many ways to screw up when belaying. In multi-pitch climbing,

slack in your tie-in or an unreliable redirect piece can result in

dangerous shock loads. When belaying on the ground, taking your brake

hand off the rope (even with an assisted braking device) can quickly

lead to a dangerous fall. Another common mistake is standing too far

away from the cliff when lead belaying— it’s easy to get dragged across

the ground when the climber falls. A big loop of slack lying in the dirt

is the lazy, incorrect way to give a “soft catch” belay. Finally, save

the crag chat until your climber is safely back on the ground.

5. Failing to knot the end of the rope

You can endlessly debate how to equalize a three-piece anchor, but it’s

more common to get seriously hurt being lowered on a sport climb than

having an anchor fail on a trad route. If you’re belaying a single-pitch

route, tie a knot in the end of the rope, tie it to the rope bag, or

tie it yourself. Do it out of habit, not just when you think the rope

might not reach. Knotting the end of the ropes is equally important when

rappelling. Slipping off the ends of rappel ropes is tragically common,

even among very experienced climbers.

REAL LIFE: In 2007, Lara Kellog, an experienced mountaineer, rappelled off the end of her rope while retreating from the Northeast Buttress of Mt. Wake in Alaska’s Ruth Gorge. She was killed after falling about 1,000 feet.

SPORT CLIMBING MISTAKES

6. Rope behind your leg while leading

Anytime you traverse, go out an overhang, or do a step-through move,

you’re in danger of putting your leg on the “uphill” side of your rope.

If you fall in this position, you’ll likely be flipped upside down.

Serious head injuries can result. Develop a “Spidey sense” about when a

leg has moved across the line, and fix the problem immediately, even if

you have to ruin your redpoint attempt to do so.

7. Poor communication

Maybe it’s windy, or the route is long, or you’re trying to climb at the

Virgin River Gorge, where the interstate noise numbs your eardrums.

Regardless, agree with your partner before you leave the ground about

your plan when you get to the anchors. Are you threading the rope

through the anchor? Lowering off draws? Planning to rappel? A

miscommunication can be disastrous.

REAL LIFE: Earlier this year, Phil Powers, executive director of the American Alpine Club and a skilled, veteran climber, fell from the top of a sport climb near Denver, where communication was likely hampered by the roar of the river and the traffic on nearby Highway 6. Powers was seriously injured but is making an amazing recovery.

8. Carabiner over an edge

When you clip a draw to a bolt, check to see where the rope-end biner

ends up. If it’s hanging over an edge, the biner could break in a fall.

Use a slightly longer or shorter draw.

9. Back-clipping

When clipping the rope into a quickdraw, make sure your end, aka the

“sharp end,” comes out of the carabiner away from the wall. If the sharp

end leads out of the carabiner toward the rock, you are “backclipped.”

There’s a higher chance that the rope could unclip itself from a

carabiner during a fall.

10. Z-clipping

There’s nothing like a closely bolted sport climb to make you feel

safe—and to increase the probability of pulling up rope from below the

previous clip and “z-clipping,” a recipe for impossible-to-move rope

drag. Make sure you pull up slack from above your last draw, even if you

have to do a series of short pulls. Bite the rope between pulls to hold

onto the slack you gain, but be careful: People have lost teeth while

clipping!

11. Using fixed quickdraws with deeply grooved carabiners

Those perma-draws in the Cave of Pump sure are nice. But look before you

clip. Rope-end carabiners on fixed draws can become deeply grooved over

time. Many grooved carabiners will hold a significant fall without

breaking, but the sharp edges of the groove can slice a rope or remove

its sheath, ruining the cord.

12. Blindly trusting bolts

It’s possible for bolts to fail. It’s very possible for old bolts to

fail. Be wary of any rusted or corroded bolts, especially at seaside

crags; saltwater breezes are very caustic to climbing hardware. A 2009

report by the UIAA showed that 10 to 20 percent of bolts in tropical

marine climbing destinations would fail if a fall generated a force of

1,125 pounds. (A “hard” lead fall may generate 2,600 pounds of force.)

Similarly, some old-school bolts from the 1980s or earlier will still

hold falls, but many won’t. Finally, give a second look to homemade

hangers, which can develop hairline fractures where they bend. When in

doubt, find a safe way to escape and choose a route with better

hardware.

13. Standing in the drop zone

Rocks frequently fall from the tops of cliffs, especially during spring

runoff or rain showers. Find sheltered belay spots if possible, and

locate your hangout areas well away from vertical or slabby cliffs, or

close underneath overhangs.

14. Toproping through fixed anchors

The sand and dirt in ropes can wear through metal, and repeated

toproping or lowering through the rings or chains on a sport climb ruins

the hardware. Always toprope through your own quickdraws, and lower

through the fixed hardware only once, when you’re done with the route.

Even better, rappel instead of lowering unless the route is too

overhanging or wandering to safely clean it while rappelling. Never

assume, however, that your partner will rappel instead of lower (see No.

7). This mistake causes many serious accidents!

15. Spraying beta

It’s awesome that you sent that climb using the tiny foot chip with your

left foot and gastoning the sidepull with your right hand. But keep it

to yourself. While no one has ever died after being sprayed down with

beta (that we know of), your big mouth could blow someone’s onsight

attempt or just ruin the peace and quiet some climbers prefer.

16. Letting your dog run free

Your dog deserves to enjoy the great outdoors with you—emphasis on with

you. Dogs running free, trampling ropes, and begging for food negatively

impact many climbers’ experience. Please control your beast.

DO: Focus on the task at hand until it’s done. Once you start putting on your harness, finish putting it on, doubled back. If someone starts talking to you after you begin tying your knot, finish the knot before conversing. Completion before distraction!

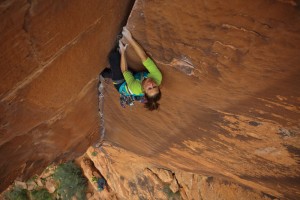

Damn—only one more wide-hands piece on my rack?! Brittany Griffith ponders her mistake. Photo by Andrew Burr

TRAD CLIMBING MISTAKES

17. Trusting all fixed slings

Just because someone else rapped off that rat’s nest doesn’t mean it’s

safe to use again. Make sure to check for sun damage (fading or

crackling) and fraying. Also, make sure a critter hasn’t chewed through

the slings hidden behind a tree or rock. Concerned? Replace the webbing

with your own.

REAL LIFE: In 2009, a webbing rappel anchor failed at the Red River Gorge, killing two young climbers.

18. Clipping into belay anchors with just a daisy chain

Daisies are great... for aid climbing. They’re not designed to hold more

than body weight, however, so they don’t belong in the belay system.

Specially designed personal anchor tethers are safer, but require

careful use; they aren’t able to stretch significantly, so a fall onto a

slack tether can severely shock-load the anchor. Tie into your anchor

with the stretchy, shock-absorbing lead rope to avoid these problems.

19. Ignoring outward pull on your first piece

Unless your belayer is directly underneath you, a fall will put outward

and upward force on the fi rst piece of pro as the rope goes tight in

the system. This may pluck out the pro and even “zipper” out all your

gear from the bottom up, as the perpendicular forces move up the wall.

Climbers have decked when all their gear zippered out. To avoid this,

make sure your first piece will hold a solid outward and upward pull.

20. Not protecting your second on a traverse

The only thing worse than leading a difficult traverse is following a

traverse that the leader didn’t protect. Be sure to leave gear along the

way to prevent a giant pendulum in case the second slips. And remember,

it’s the gear placed after cruxes that protects the second on those

moves.

21. Failing to place enough gear above a ledge

It’s critical to closely space your gear when you’re leading above a

ledge, especially high on a pitch where you can expect significant rope

stretch in a fall.

REAL LIFE: In 2005, a climber on the Northwest Books (5.6) in Tuolumne Meadows, California, hit a small ledge in a lead fall, breaking one ankle and spraining the other. It happens frequently. Sew it up above ledges and save your ankles.

22. Using all the same size gear in the belay

If you’re building a belay at the base of a long, sweet finger crack,

don’t use all the finger-sized pieces in the anchor. With a little

creativity, you can often figure out a way to save the crux-protection

pieces for the next lead.

23. Carrying no tied slings

That fistful of skinny sewn slings may save weight, but they’re not your

first choice for leaving behind as rappel anchors when you have to

bail. A tiedwebbing runner is easy to un-knot for threading through a

hole, tying around a tree, or adjusting anchor length for equalization.

With a sewn sling, you may have to cut the webbing to build your anchor

(you did clip a lightweight belay knife to the back of your harness,

right?), and it’s tough to tie those slick-as snot suckers back

together. Keep a couple of tied slings on your rack, just in case.

24. Lowering directly off webbing

Never run a piece of moving nylon (your rope, for example) through a

sling without putting a carabiner or metal ring between the two—the

sling can burn in seconds under a taut, moving rope. Rappelling directly

off slings always is perilous; if the rope slips—due to unequal tension

on different-diameter ropes, for example—it can cut the sling. Improve

such anchors with a quick link or a carabiner taped closed.

25. Forgetting the nut tool

Leaving behind gear on a pitch is an expensive bummer.

26. Forgetting your headlamp

Even if you don’t think you’ll need a headlamp, stick one in a pocket or

clip it to the back of your harness for long climbs. A light can make

the difference between a cold, thirsty bivy and a pleasant evening hike

back to camp.

27. Wearing a backpack in a chimney

Many classic lines, such as Epinephrine at Red Rock, Nevada, or the Steck-Salathé

in Yosemite Valley, have long chimney sections. If you hope to have any

fun squeezing up the slots, don’t wear a pack full of water and energy

bars. If you must carry a pack, hang it by a sling from your belay loop

as you climb short chimney sections.

DO: Back-clean when needed. If you notice that you’ve created heinous rope drag with your first few placements (sometimes unavoidable if you want to protect the climbing), place a couple of pieces of solid gear and down-climb or lower to remove the troublesome gear. If you try to fight it, the drag will only get worse. You may not be able to reach a belay, or be able to pull up the rope to properly belay your second. You’ll save time and frustration if you fix the problem early.

No chit-chat, no bullshit. Louis Koppel gives a proper spot in Hueco Tanks, Texas. Photo by Ryan Wedemeyer

BOULDERING MISTAKES

28. Lame spotting

You shouldn’t text and drive. You also shouldn’t drink water, play with

your smart phone, or check out that hot gal/guy while spotting. Focus

100 percent on keeping the climber safe.

29. Forgetting to check your descent

Nothing is worse than manteling out the final moves on your highball

boulder project (nice send), only to realize you don’t know how to get

down—it’s possible that you just climbed the easiest route to the top.

Scout the descent before your ascent.

30. Climbing with dirt on your shoes

Dirty shoes don’t stick well, and they grind grit into the footholds and

polish them. Wipe your shoes clean before you start, and step directly

from your pad or a nearby rock onto the problem.

31. Leaving tick marks

Many climbers mark hand or footholds with a bit of chalk—sometimes with a

big, ugly line. If you prefer to climb with this kind of visual aid,

fine, but make sure you brush off your graffiti before you leave.

ICE CLIMBING MISTAKES

32. Falling

A leader fall on a steep sport climb is part of the game. On ice, it’s a

dangerous mistake. A crampon point can easily catch, snapping your

ankle, or an ice axe can skewer your thigh. Before leading on ice, learn

how to test your placements, how to conserve your strength, and how to

bail if you realize you’re in over your head. The leader must not fall!

33. Belaying directly below an ice climb

33. Belaying directly below an ice climb

Heavy chunks of ice often rain down below the leader, and icicles may

snap off without warning, especially on sunny climbs. Save yourself the

headache (literally) and, whenever possible, set up your belay off to

the side or under an overhang.

REAL LIFE: Ice climber Rod Willard was tragically killed in 2002 while belaying in Vail, Colorado. A huge piece of ice fell from above and hit him, causing fatal injuries.

If you set up a toprope anchor using ice screws (three is a minimum), check them regularly to make sure they aren’t melting out, especially on sunny days. You can insulate the screws by packing the tops with snow.

Much as you’d like to snag the first ascent of the season, climbing a poorly formed ice route is extremely dangerous— and it can also ruin the climb for later ascents.

It’s tempting to place screws as high as possible, and if you’re standing on a ledge, it’s no problem. But when you’re leading steep, pumpy ice, place the screw at chest level, where you can generate maximum leverage to drive in the screw quickly and efficiently.

37. Not wearing eye protection

There’s nothing like an adze or ice shard to the eyeball to really darken your day. Wear sunglasses, goggles, or a face shield.

38. Ignoring avalanche conditions

Ice climbs often form in or below gullies that can funnel snow and make

for high avalanche hazard, and the approaches and descents to climbs

also may be avy zones. Check whether your climb is in avalanche terrain,

and evaluate conditions locally before you head out.

REAL LIFE: In 2009, ice climbing icon Guy Lacelle was killed after finishing an ice route in Hyalite Canyon, Montana. Lacelle was apparently resting at the top of the climb when a party above him triggered an avalanche, which swept him back down the cliff.

DO: Dry and sharpen your tools and crampons after every outing. The hard steel of crampon points and ice-tool picks will rust if left in your pack while damp. Take them out, dry them, and tune the edges with a few strokes of a file. (It’s a lot easier to maintain an edge than it is to create a new edge on a dull pick.) Finish with a once-over witha lightly oiled cloth for rust resistance.

Roping up can protect your party on soft snow, but please do a reality check—see number 41. Photo by Andrew Burr

MOUNTAINEERING MISTAKES

39. Not acclimatizing

Even if you’re as fit as a marathon runner, altitude does not care. The

body needs time to adjust to low-oxygen living. Spend the first days of

your expedition climbing high and then sleeping down low. Pay attention

to the early signs of altitude sickness: headaches, nausea, and lack of

appetite. If you feel mildly ill, it’s a good idea to stay at the same

elevation until you feel better before you continue the ascent. If you

have more severe signs—a splitting headache or a wet cough—descend

immediately.

40. Going unroped in crevassed terrain

Tie in even if crevasses look well covered or if you’re following

others’ tracks. Snow bridges collapse without warning. And make sure you

have the tools and skills you’ll need to rescue your partner or

yourself from a crevasse.

41. Roping up without pro on steep, firm snow

Roping up while moving together on steep, snowy terrain is often a good

idea—but not always. If you don’t have pickets, ice screws, or other pro

between you, and if the snow conditions don’t allow reliable

self-arrests, roping together adds risk for the entire team. Don’t let

the presence of the rope trick you: You may be safer soloing.

REAL LIFE: In 1981, a team of seven Japanese climbers, roped together, was descending from an unsuccessful attempt on Gongga Shan (7,590 meters) in China. When one member slipped, all seven fell to their deaths.

42. No plan for a whiteout

Weather changes fast, and straightforward terrain gets tricky when you

can’t see. Always have a plan for retreating safely when visibility

drops to nil. Take back bearings with your compass. Leave wands to mark

your route. Use a GPS to mark waypoints.

43. Deyhdration

On big, snowy mountains, cold temps can suppress thirst, but being

hydrated helps you perform better and acclimatize quicker. Drink before

you get thirsty, drink often, and drink copiously.

Snow blindness is temporary, but it can paralyze your ability to function, and it hurts like a bitch.

Life on the glacier is all about reflected sunlight. Don’t forget to slather up between your nostrils.

AID CLIMBING MISTAKES

46. Not tying in below your jumars

Having an ascender pop off as you jug a fixed line is not all that

uncommon—having two pop off could be lethal. Don’t forget to tie in to a

locking carabiner on your belay loop as you go; every 30 feet on steep,

clean ascents is about right. Always tie a back-up before tricky

overhangs or traverses.

47. Looking at a placement while bounce testing

What’s worse than having your piece pull when you test it? Having that

piece smack you in the face. Turn the top of your helmet toward that

mank.

48. Bringing too much (or not enough) water

Nothing slows a multi-day climb like hoisting a swimming pool in your

haul bag. On the other hand, you’ll also be slowed to a crawl by

becoming so dehydrated that you start to consider drinking your own

urine. Carefully estimate water needs based on the sunniness of the

route, season, and water content of other foods that you’re bringing

(soup for dinner = less water). Three quarts of water per person per day

is a good rule of thumb in the late fall and early spring; a gallon or

more may be appropriate on sunny walls in August.

49. Passing another party when you’re not actually faster

Passing a slower party is copacetic, with their consent. But make sure

they’re actually slower, and not just grappling with a crux that would

slow your team just as much. If you crowd a team above you only to stall

out after passing, admit your mistake and offer the other team its

original front position.

50. “Soiling” your partner

Don’t allow urine or excrement to touch your partner, your rope, or any

of your gear. Plan ahead, account for wind, and find a stable spot. Most

“emergencies” are easily avoided by heeding the warning signs, just as

you would at home or at work.

Comments

Excellent. I could only add under traditional climbing: "Having retreat gear and the moxy to make your own way" although this falls into not exceeding abilities. The most appalling rescue I've heard of in recent years was the two goobers helicoptered off Epinepherine with NO injuries and weather was not a factor. They got tired and thirsty so they pulled out the phone and called the grownups. Staggering.

Gerald Wilson - 05/23/2014 12:16:42waooooooooooooo excelent

oMAR mARTINEZ AC - 05/04/2014 4:01:22@dtarman - what do you mean by "top belay"? If you mean belaying a second from the top of a pitch eg on a multipitch climb, you can prevent getting yanked up by belaying directly off the anchor using a device such as an ATC guide or Reverso.

marmen - 05/03/2014 12:14:36I'd like a discussion of top belays. Even when the anchor seems solid, getting pulled over the top and slammed into the rock when the bottom climber falls is unpleasant. I recently broke a rib giving a top belay.

dtarman - 05/02/2014 4:29:30Re. metal to metal. There is nothing wrong with it. Just don't chain 3 biners. Metal-to-metal itself doesn't reduce the strength. How do you think the biners are tested on the pullers? They are being pulled by metal rods!

Deling Ren - 05/01/2014 5:48:22Since the conversation has turned to metal on metal--it is worth pointing out that you must never chain three biners together. If you want to know why then clip three biners together, hold both ends and twist in different directions. One of them will open and the connection will fail.

Bob Margulis - 05/01/2014 5:07:28Graffiti? That's a little drastic, isn't it? We're not talking about graphic art.

Garth - 05/01/2014 1:04:46Graffiti? That's a little drastic.

Garth - 05/01/2014 1:03:03No. 5 - Knotting the end of the ropes is equally important when rappelling. There may be some situations where you decide not to do this, such as a windy day on a broken rock face with lots of cracks, and spires. There is a possibility that the wind could blow the end of your rope into a wedge shaped crack, which could jamb the knot when you pull on the rope.

Colin - 04/30/2014 5:11:46Hello Nancy, Metal-on-metal connections are safe, but why not use a proper length sling/draw/rope? More gear means the more likely to make mistakes and/or accidentally unclip.

Harald - 04/30/2014 6:45:20Thanks too much

Grotto - 04/29/2014 8:24:56Adrian!

Jimbo - 04/29/2014 6:28:08This is the greatest thing I've ever read. As a climber, I agree with absolutely everything said here...especially the daisy chain anchor. It's what most gyms teach to pass "belay tests", but they don't think beyond their own walls. A heavy lead fall vs.light belay yanked to a daisy chain? Snapzilla. Terrific article, mate!

Tomi - 04/28/2014 6:45:56There isn't anything absolutely wrong using 'metal on metal' Nancy, most the traditional climbing and aid climbing world relies on it even, but depending on the draws it could definitely be less than ideal or even unsafe. Basically, take two biners and rotate them a bunch and watch how easy they come undone, in that lies the danger of metal on metal.

Raz Peel - 10/31/2013 12:06:47